Pompeii Exhibit

In the spring, we heard about a new exhibit coming to the Legion of Honor museum in San Francisco, called “Last Supper in Pompeii.” The exhibit was a collection of food-related artifacts from Pompeii: mosaics, frescoes, carbonized ingredients and loaves of bread, cooking implements, and much more. This exhibit combines TWO of my great interests: Roman history, and food history! And we’d visited Pompeii, so we had a bunch of context for the artifacts.

We got timed tickets for June 5th, shortly before school got out. (Museums that were open during this period were almost all timed-entry, to keep the numbers of visitors down during the pandemic.)

We got there before our time (and even got good parking, which is saying something in San Francisco), then got into the wing with the exhibit. I had an absolutely marvelous time. I did a slow pace, reading every sign, examining every artifact, and taking it all in, installing it deep into my brain.

A highlight for me was seeing a loaf of carbonized bread: when archaeologists excavated a baker in Pompeii, they discovered dozens of carbonized loaves, some still in the oven. These loaves, called Panis Quadratus, were round loaves divided into eight segments. I’ve read the blogs of bakers trying to recreate them, puzzling out how the divisions were made (the bread may have been sold in segments?), and whether there was a rope around the ‘waist’ of the bread (to contain the bread? or for carrying?), whether there was a hole in the center (maybe for carrying? or to help the center cook?)

There was also a display of other carbonized ingredients, which showed what people in Pompeii were actually eating: walnuts, almonds, figs, dates, and olives; but also fruits like pomegranates, plums, and grapes; and seafood like mussels and oysters; grains like wheat, spelt and millet; and pulses like lentils and beans.

There was even a cast of a pig which had died in the eruption, and had been preserved with plaster (like the human casts.) The pig was much smaller than modern breeds.

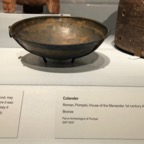

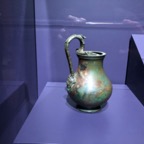

Pompeii’s streets were lined with shops, restaurants and bars, which produced all kinds of goods, such as clothing, furniture, food, and drink. The food shops basically had completely open fronts, which allowed lots of light and air to come in. These fronts were closed with sliding poles every night. The exhibit had a number of items from these shops, like a portable stove and a countertop.

The portable stove was a flat terra cotta rectangle with low walls, like a baking dish, with three round, partially-walled alcoves at one side, each with terra cotta tabs sticking out over the alcove. The shop owner would light a little fire in each alcove and balance a pot on top! Presumably (I am guessing) the large rectangular area was for fire management: the shop owner could start a fire on the larger rectangular area then push a piece of the fire into an alcove to heat a specific pot, and could scrape the ashes back out as needed.

They also had a dormouse container! Dormice were delicacies that were served in wealthy people’s homes. The ‘edible dormouse’ is actually a rather large rodent – about the size of a squirrel. These would be captured in the autumn when they were fat in preparation for hibernation. Each one would be placed in a special container, called a dolia. This was a big, terracotta jar, perhaps two feet tall, which was pierced all over with holes for ventilation. It had internal ramps spiraling up the inside walls for the dormouse to run up and down, and a little hollow where food could be provided – they were fed walnuts, chestnuts, and almonds. There were several ways to prepare dormice – one was to stuff it with pork, pepper, fish sauce, and nuts.

At the very end of the exhibit was a human figure – a resin cast made of a woman who died in the eruption. I’d wanted to see this cast for a long time, as it contains much more detail than the plaster casts.

Basically, the victims of the eruption were encased in ash, which formed a hard shell around the body, preserving the shape and position of the body including details like folds of clothing, shoes, etc. Then the body decomposed within this shell, but the cavity itself preserved the imprint of the body.

An excavator in 1870 realized that he could preserve the imprint of these bodies by filling the cavities with liquid plaster. Most of the Pompeii casts are made with plaster like this. However, in 1984, a different material was used -- epoxy resin – which is transparent. This preserved the details of the cavity, and also allows one to see inside the cast and glimpse bones, teeth, and other items that may have survived, like jewelry and coins. Resin is better than plaster, because it lets you see in, and because it doesn’t react with the bones themselves. Plaster contains lime, which reacts with the bones. But resin is also much more expensive, and more difficult to do in the field, so only one resin cast has been made.

A study of this cast, which was performed in Australia, revealed that this was a woman in her early 40’s, with a healed broken arm, four cavities in her teeth, and the beginnings of a tooth abscess above one premolar. She had a small purse clutched in one hand, which contained coins and jewelry, and she had a bracelet on her arm.

The exhibit ended with a 9-minute movie that reconstructed what the eruption would have looked and sounded like from a vantage point in Pompeii, which was very moving.

You can actually watch it yourself here:

https://aeon.co/videos/from-eruption-to-obliteration-the-sights-and-sounds-of-48-fateful-hours-in-pompeii

After the exhibit we had a picnic on the grounds of the museum, then drove back down the peninsula. As it was still just midafternoon, we stopped in Palo Alto for ice cream cones at Salt and Straw, then, since we were already doing musemy things, we popped over to the Rodin sculpture garden at the Cantor art museum.