Boston: Fine Art Museum

The next day, July 29, we visited the Boston Art Museum. We walked through a rose garden on our way there, which was beautiful, and as it was due to be windy and cool later in the day it was good to be outdoors when the weather was lovely.

At the museum we looked at the different wings available, and conferred on which wings to see. Everybody gets to pick a wing in a museum like this, and we do our best to see what everyone wants to see, prioritizing unique exhibits and exhibits that people feel really strongly about.

Ellie wanted to see the exhibit on historical musical instruments, so we started with that. We saw an amazing collection of instruments, including lots of instruments in the harpsichord-piano family that I never knew existed. It is a bit like seeing prehistoric animals in a natural history museum: you can see all the forms that don’t exist any more, ones that became dead ends, or were the ancestors of more modern forms.

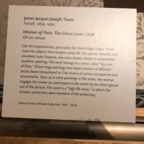

Then we saw some French Impressionists. We’re sort of tracking them across the world, seeing an exhibit here and an exhibit there all over the place.

We left the museum to go out to lunch at another branch of Tatte, the same bakery we had discovered the day before in Charlestown. It was delicious!

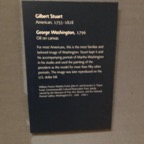

After that we saw some early American paintings. These don’t usually interest me very much because they are often portraits of rich people that are stylistically derivative of British paintings of the period. But I was wrong: the Boston collection had historical paintings of people and events, including famous aintings of George Washington and Paul Revere! So I REALLY enjoyed this exhibit.

A highlight was talking with a guy in front of a painting of a blacksmith. This guy had a LOT of strong feelings about this painting, and was angry about its info paragraph. It’s unusual to find someone with strong feelings about a 200 year old painting. Most passions have died down after two centuries, but not for this guy. He told us the blacksmith’s story, about how he was falsely accused and falsely imprisoned, and showed us all the clues and hints that were hidden in the painting itself.

In a nutshell, this was a painting of one Patrick Lyon, who was born in Scotland in 1769 and emigrated to America as a young man in 1793. He became a locksmith. He was commissioned to construct new locks for the vault doors of the Bank of Pennsylvania in 1798. He made the locks, put them into the vault doors, and these doors were installed on August 13, 1798.

Now, during this same summer (and for several summers before this) a yellow fever epidemic was tearing through the Philadelphia, and many people fled, including President John Adams, Congress – Philadelphia was the capital at the time -- and many of the city’s inhabitants. A few days after the new locks were installed on the bank doors Pat Lyon fled the epidemic too, along with his 19-year old assistant Jamie, heading to Delaware. Unfortunately, Jamie died of yellow fever just two days after they arrived.

While Pat was in Delaware, on the night of August 31, when much of the city was deserted, the Bank of Pennsylvania was robbed. There were no signs of a break in, and the locks were undamaged. Pat was accused of having broken into the bank by having made a secret set of keys for himself, despite the fact that he was in Delaware at the time of the robbery. Pat returned to Philadelphia to clear his name, but he was arrested without evidence and thrown into jail.

The robbery turned out to have been an inside job committed by the owner of the bank building and the night watchman. The night watchman died of yellow fever just days after the robbery, but the owner came under suspicion when he made a bunch of large deposits (back into the same bank!) The owner confessed and was pardoned on the condition that he return the money. He returned MOST of it and was never prosecuted further.

Meanwhile, Pat Lyon was still in jail, even after the owner’s confession. The high constable refused to release him. Finally, a grand jury refused to indict Lyon and he was released in 1799, after having spent several months in jail. He filed a suit for malicious prosecution, and it went to trial; the jury found in his favor and awarded him damages which were settled out of court.

So this portrait was of Patrick Lyon: he is dressed as a blacksmith, standing in his shop, with a hammer and anvil and other tools around him. The painting is full of clues and hints about his past. The jail is visible through the window, to commemorate his unjust imprisonment. Jamie, his young assistant, is behind him. The cupola of the jail has a key on it. On a piece of paper in the shop is a geometric drawing of the Pythagorean theorem.

The guy who told us this story was indignant on Lyon’s behalf. He went on to tell us about a portrait of Washington on the far side of the room, in which you could see a reflection in Washington’s buttons!

It turns out that this guy was a high school history teacher, who had regularly brought his classes to the Boston Museum of Fine Art. He couldn’t bring them any more due to the pandemic. He missed bringing them… but he also remembered that when he brought them they were frequently bored. So I think it was rewarding for him to talk to a family of five who were hanging on his every word and asking him lots of questions!

We went on to see a famous portrait of Paul Revere, and the Sons of Liberty bowl that he made as a silversmith in 1768.

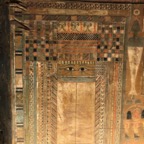

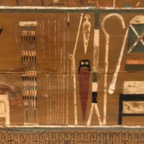

Then we ended up in a room with Egyptian antiquities, which was QUITE a shift in time period and location, but it was also fascinating – they had the wooden coffin of a Governor in it, from 2010-1961 BC (almost exactly as far before year 0 as we are after it today). This coffin was amazing because of the incredible detail and preservation of the paintings on it. I stayed in that room a long time, reading every panel and soaking it in.

In the late afternoon we headed back on the metro. At home I made another sauteed vegetable medley on a bed of lettuce with a poached egg on top, a very typical dinner which everyone enjoyed very much.